IRAQ

The future? First thing is to survive

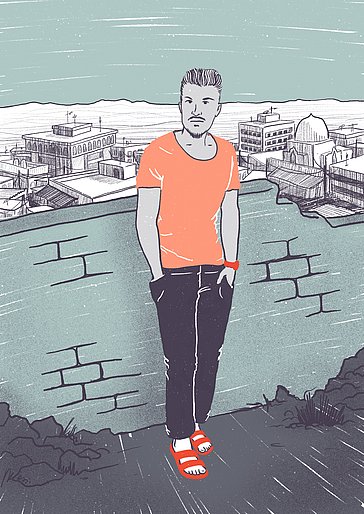

Hussein al-Māwardī: Iraq – Germany – hidden somewhere

Some stories are difficult to write down. Because memories are fraught with gaps or because the experiences fragment the personality itself. The story of Hussein al-Māwardī* is one of these.

He is in his early 30s, married and has two children. He lives apart from his family, however, somewhere in the desert in Iraq, where he earns a meagre wage as a simple labourer. He used to live in Baghdad, but that was before he fled. Now he has to hide. He has to be careful and that is how he tells his story – carefully, quietly and with a lot between the lines.

Asylum no, toleration yes

In 2015, Hussein fled Iraq. His brother-in-law, a Shiite who was not sympathetic to him, a Sunni, had threatened to kill him. After Hussein refused to take to the streets for the pro-government party, in which his brother-in-law is an important figure, his brother-in-law’s subordinates beat him up and demanded that he separate from his wife and their children. Fearing for his life, Hussein set off for Europe. Across the Mediterranean to Greece. From there he proceeded on foot most of the time, making it to Germany, where he applied for asylum. In 2017, his application for asylum was rejected and he received a toleration order. This meant he could not be deported to Iraq and was therefore safe for the time being. As a tolerated person, however, he had no right to family reunification. So there was no legal way for him to bring his wife and children to Germany.

Back, but in hiding

In 2018, Hussein had to return to Iraq because close relatives had had a serious accident. When he applied for asylum, he had already been informed about the possibility of a “voluntary” return, so he contacted a counselling centre. He was happy that through the programme his flight would be paid for and he was promised support for his re-settlement. Soon he travelled back to Iraq, not because he wanted to, but because he had to, as he puts it. In order not to endanger anyone, he lived separately from his family and kept a low profile. He received USD 1,600 in start-up aid from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), which he had to advance himself and was only allowed to spend on furnishings. He bought a refrigerator and was grateful, even though he was promised more support in Germany. But what he needs most of all is something no reintegration measure can offer him, which is protection and personal security. What would help him would be a legal opportunity to return to Germany with his family. But that is not provided for in the German immigration system.

Not an empty threat

At the end of 2019, there were uprisings in Iraq to protest against corruption and clientelism, as a result of which the government had to step down. Hussein also took to the streets to protest. He was arrested by the police and photographed. That is how his brother-in-law learned that he was back in the country and had him put on a death list. Hussein decided to go into hiding. But when his mother fell seriously ill, Hussein went to visit her. He was recognised and shot in the back. Hussein survived, although seriously injured, and was in hospital for a long time. After his release, he sought refuge again in the countryside, where he hoped that no one would find him. If there were a safe way, he would immediately want to start a new life with his family somewhere else. The reintegration measures have not fundamentally improved his living situation. “How could they?” asks Hussein. “For me to be able to live here, the whole country would have to change.”

* The names have been changed by the editors.